Archive Gallery

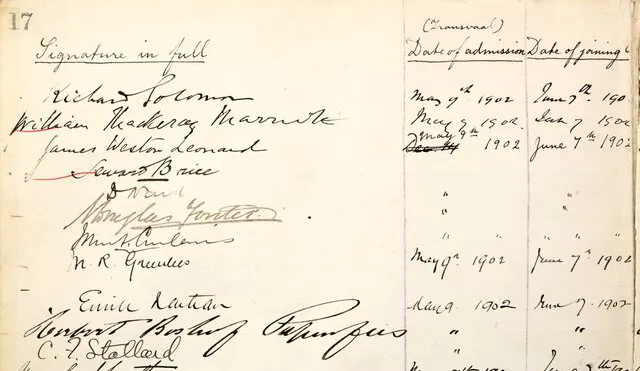

The founding of the Johannesburg Bar is by, tradition, the day upon which Richard Solomon signed the Membership Book on 7 June 1902. The book was used to record every new member until June 1995 when a new book was opened.

In the report of the Johannesburg Local Bar Council of 14 November 1919 it was recorded that at the Half-yearly Meeting it had been resolved that the question of separation would be dropped but the Local Rules would be changed to provide for two Joint Secretaries and Treasurers chosen from the Pretoria and Johannesburg members respectively. The subscriptions of the members would be held in separate funds with the existing fund being divided between Pretoria and Johannesburg pro rata. Furthermore, 'all powers exercisable by the Council would now be exercisable by Pretoria or Johannesburg members acting separately, provided that due notice be given to the Joint Secretary and Treasurer residing in the other Division and provided that any actions affecting members in the other Division would be discussed at a General Meeting of the two divisions'.

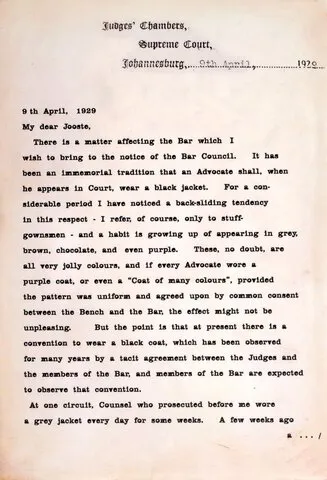

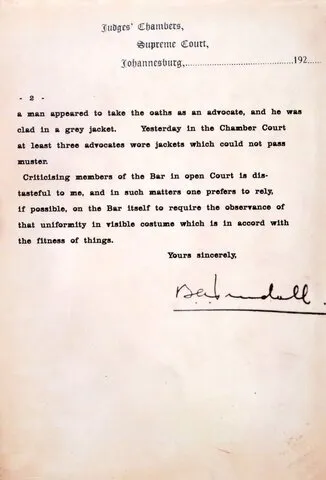

Do counsel want to be seen? How to dress up properly. This letter expressing dismay at sloppy dressing by counsel when appearing in court is a vintage bleat that has retained its flavour over generations. The new practice manual of the SGHC echoes some of these sentiments, and offers guidance on the proper degree of care to be taken over doing up buttons. (See: Practice Manual of the South Gauteng High Court: 4:4 (First issue: 2010, February)

Do counsel want to be seen? How to dress up properly. This letter expressing dismay at sloppy dressing by counsel when appearing in court is a vintage bleat that has retained its flavour over generations. The new practice manual of the SGHC echoes some of these sentiments, and offers guidance on the proper degree of care to be taken over doing up buttons. (See: Practice Manual of the South Gauteng High Court: 4:4 (First issue: 2010, February)

Do counsel want to be seen? How to dress up properly. This letter expressing dismay at sloppy dressing by counsel when appearing in court is a vintage bleat that has retained its flavour over generations. The new practice manual of the SGHC echoes some of these sentiments, and offers guidance on the proper degree of care to be taken over doing up buttons. (See: Practice Manual of the South Gauteng High Court: 4:4 (First issue: 2010, February)

Do counsel want to be seen? How to dress up properly. This letter expressing dismay at sloppy dressing by counsel when appearing in court is a vintage bleat that has retained its flavour over generations. The new practice manual of the SGHC echoes some of these sentiments, and offers guidance on the proper degree of care to be taken over doing up buttons. (See: Practice Manual of the South Gauteng High Court: 4:4 (First issue: 2010, February)

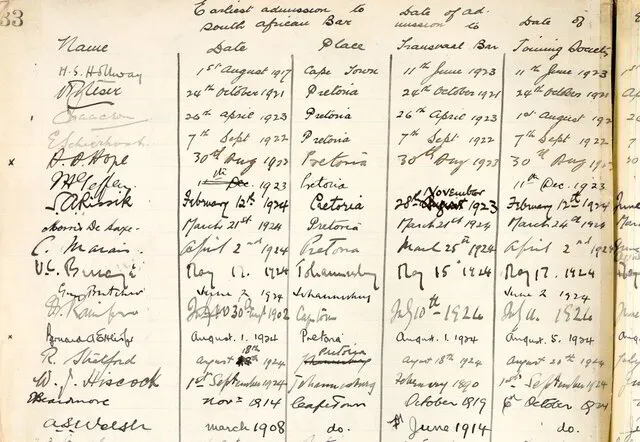

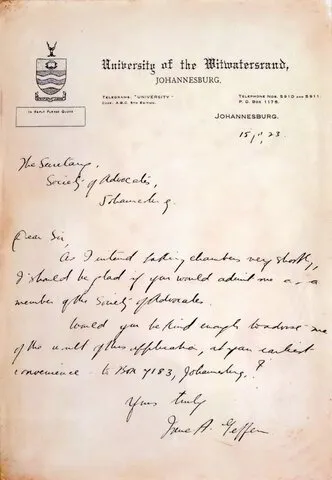

Do we want women in our Bar? The first woman member. The first woman to be admitted to membership was Irene Geffen in 1923. The document displayed is her application. The date is significant: 15 November 1923. The legislation necessary for a woman to become an Advocate came into force on 26 March 1923, less than six months earlier. That Act was necessary to upset the decision, given 11 years before, in Incorporated Law Society V Wookey 1912 AD 623 which declared that 'persons' in the Cape Charter of Justice, which regulated admission to the legal professions, meant only men and excluded women. (See Karen Blum SC: 'Portia Today' in Consultus, 1990, April, p 12). Blum SC was the first Woman to take Silk at the Johannesburg Bar in 1984.

Do we want to honour our old soldiers? Silk for Soldiers after WWII. During the Second World War several members went up North. Only volunteers served outside the country and wore the 'Red Tab' to mark the fact. At the end of the war these men, having sacrificed years of their careers, returned to pick up their practices. While away, they unopposed matters and members who remained in practice 'held' those briefs with the fees going to the absent members' families. A now abrogated convention about holding briefs for absent members which lasted into the 1980s originated under these circumstances. This document signals the keen competition for work in the post-war world and an equally keen sensitivity that those who had bled should get preference for silk over those who had stayed at home and read.

However, it is questionable whether it is true that the Johannesburg Bar, as a distinct Society of Advocates, was truly 'founded' then. The genesis of what we call the Johannesburg Bar is far more complex. (See: R L Selvan: 'Early Days at the Johannesburg Bar', Consultus, 1994, October, P115). This is one among many other curious or intriguing facts which emerge from poring over the archival records.

Do we want to honour our old soldiers? Silk for Soldiers after WWII. During the Second World War several members went up North. Only volunteers served outside the country and wore the 'Red Tab' to mark the fact. At the end of the war these men, having sacrificed years of their careers, returned to pick up their practices. While away, they unopposed matters and members who remained in practice 'held' those briefs with the fees going to the absent members' families. A now abrogated convention about holding briefs for absent members which lasted into the 1980s originated under these circumstances. This document signals the keen competition for work in the post-war world and an equally keen sensitivity that those who had bled should get preference for silk over those who had stayed at home and read.

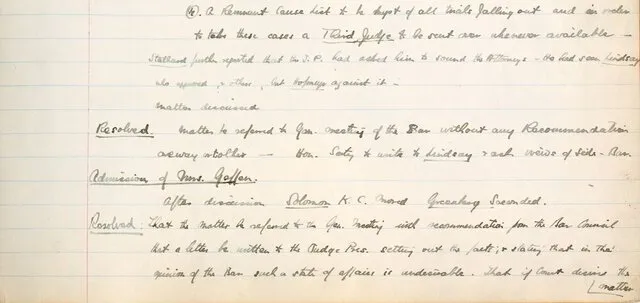

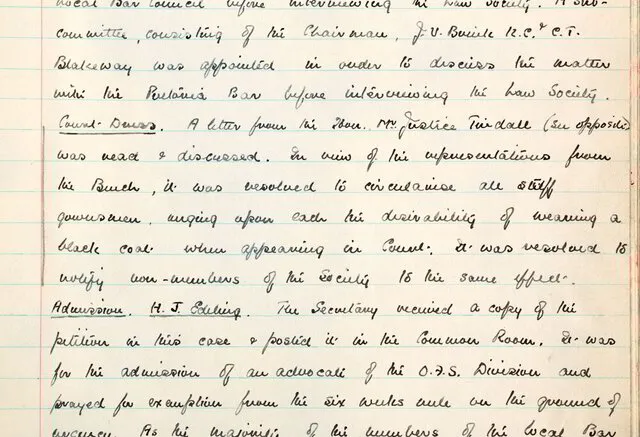

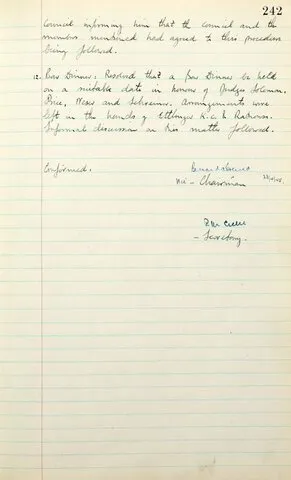

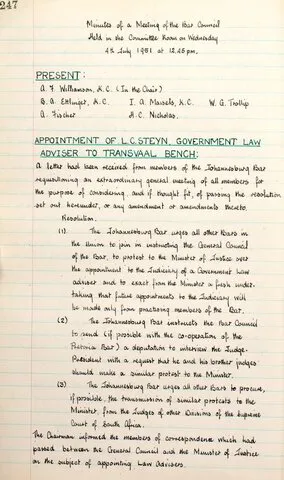

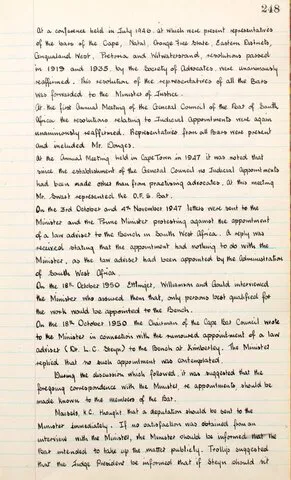

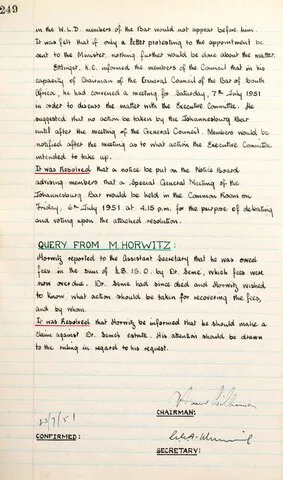

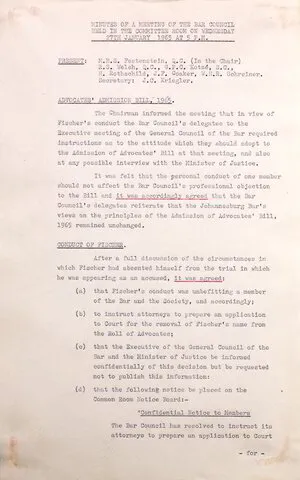

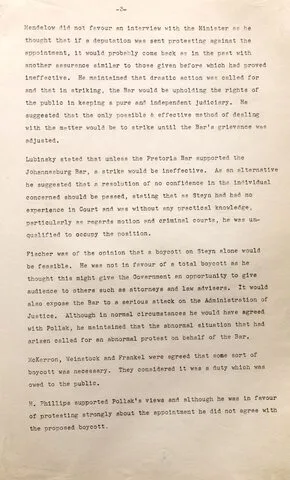

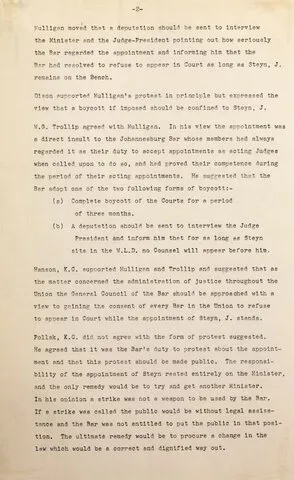

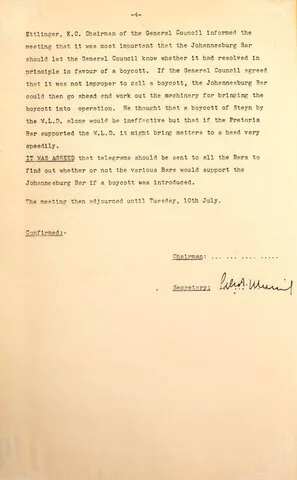

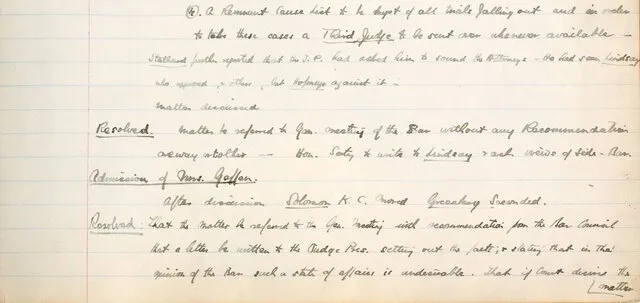

Can we boycott this Judge? State Law Adviser, L C Steyn, becomes a Judge. These minutes reflect the heat of the crises that arose when the National Party Government, then about two years in power, chose one its favoured sons, L C Steyn, the then chief State Law Adviser (later Chief Justice) to be a judge. the profession's repugnance towards the Executive's attempt to breach the sacred unwritten rule that civil servants were not eligible for judicial office is illustrated. The Nationalists did not do so again until the late 1970's when A Lategan, Attorney-General of the Cape, was appointed. The controversy has loomed again in 2010 with the appointment of a Deputy National Director of Prosecutions as an Acting Judge, apparently at his request to the Minister of Justice.

Can we boycott this Judge? State Law Adviser, L C Steyn, becomes a Judge. These minutes reflect the heat of the crises that arose when the National Party Government, then about two years in power, chose one its favoured sons, L C Steyn, the then chief State Law Adviser (later Chief Justice) to be a judge. the profession's repugnance towards the Executive's attempt to breach the sacred unwritten rule that civil servants were not eligible for judicial office is illustrated. The Nationalists did not do so again until the late 1970's when A Lategan, Attorney-General of the Cape, was appointed. The controversy has loomed again in 2010 with the appointment of a Deputy National Director of Prosecutions as an Acting Judge, apparently at his request to the Minister of Justice.

Can we boycott this Judge? State Law Adviser, L C Steyn, becomes a Judge. These minutes reflect the heat of the crises that arose when the National Party Government, then about two years in power, chose one its favoured sons, L C Steyn, the then chief State Law Adviser (later Chief Justice) to be a judge. the profession's repugnance towards the Executive's attempt to breach the sacred unwritten rule that civil servants were not eligible for judicial office is illustrated. The Nationalists did not do so again until the late 1970's when A Lategan, Attorney-General of the Cape, was appointed. The controversy has loomed again in 2010 with the appointment of a Deputy National Director of Prosecutions as an Acting Judge, apparently at his request to the Minister of Justice.

Can we boycott this Judge? State Law Adviser, L C Steyn, becomes a Judge. These minutes reflect the heat of the crises that arose when the National Party Government, then about two years in power, chose one its favoured sons, L C Steyn, the then chief State Law Adviser (later Chief Justice) to be a judge. the profession's repugnance towards the Executive's attempt to breach the sacred unwritten rule that civil servants were not eligible for judicial office is illustrated. The Nationalists did not do so again until the late 1970's when A Lategan, Attorney-General of the Cape, was appointed. The controversy has loomed again in 2010 with the appointment of a Deputy National Director of Prosecutions as an Acting Judge, apparently at his request to the Minister of Justice.

Can we boycott this Judge? State Law Adviser, L C Steyn, becomes a Judge. These minutes reflect the heat of the crises that arose when the National Party Government, then about two years in power, chose one its favoured sons, L C Steyn, the then chief State Law Adviser (later Chief Justice) to be a judge. the profession's repugnance towards the Executive's attempt to breach the sacred unwritten rule that civil servants were not eligible for judicial office is illustrated. The Nationalists did not do so again until the late 1970's when A Lategan, Attorney-General of the Cape, was appointed. The controversy has loomed again in 2010 with the appointment of a Deputy National Director of Prosecutions as an Acting Judge, apparently at his request to the Minister of Justice.

Do we want to honour our old soldiers? Silk for Soldiers after WWII. During the Second World War several members went up North. Only volunteers served outside the country and wore the 'Red Tab' to mark the fact. At the end of the war these men, having sacrificed years of their careers, returned to pick up their practices. While away, they unopposed matters and members who remained in practice 'held' those briefs with the fees going to the absent members' families. A now abrogated convention about holding briefs for absent members which lasted into the 1980s originated under these circumstances. This document signals the keen competition for work in the post-war world and an equally keen sensitivity that those who had bled should get preference for silk over those who had stayed at home and read.

Can we boycott this Judge? State Law Adviser, L C Steyn, becomes a Judge. These minutes reflect the heat of the crises that arose when the National Party Government, then about two years in power, chose one its favoured sons, L C Steyn, the then chief State Law Adviser (later Chief Justice) to be a judge. the profession's repugnance towards the Executive's attempt to breach the sacred unwritten rule that civil servants were not eligible for judicial office is illustrated. The Nationalists did not do so again until the late 1970's when A Lategan, Attorney-General of the Cape, was appointed. The controversy has loomed again in 2010 with the appointment of a Deputy National Director of Prosecutions as an Acting Judge, apparently at his request to the Minister of Justice.

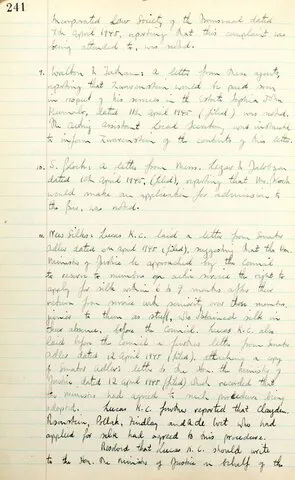

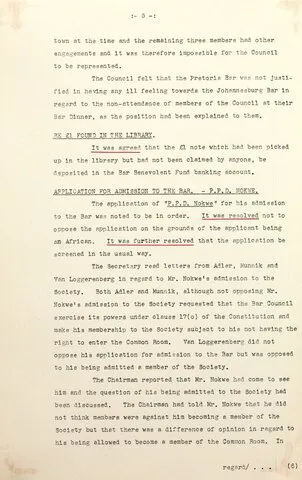

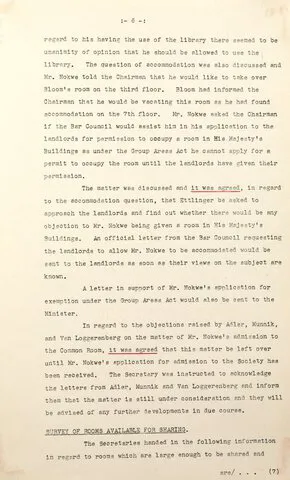

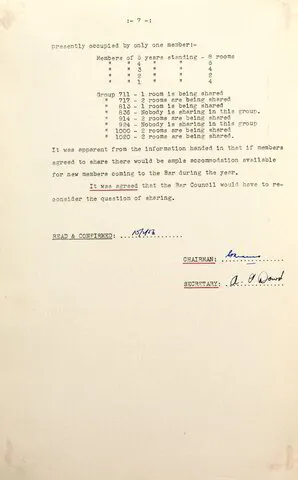

Do we want Blacks in our Bar (again)? The first Black member Duma Nokwe was the first person of Black African descent to be admitted to the Bar. Nokwe's role in the liberation struggle and his death in exile are well known. Duma Nokwe was honoured by the erection of his bust in the grounds of the Johannesburg Bar Group that bears his name in memoriam. Nokwe signed the Book on 9 March 1956. The minute reflects the values of the various decision makers at the time. He was admitted to membership, the colour bar having been abolished in 1950, as mentioned above, he could use the library, but was not allowed into the common room. (See Browde and Selvan: Supra, at pp 9- 13) Nokwe was, subsequent to becoming a member, harried by the State and prevented from taking up chambers, on the premise that he ought to 'be among his own people'. (See: Peter Pauw: 'Apartheid and the Bar', Consultus, 1992, April, p 22)

Do we want Blacks in our Bar (again)? The first Black member Duma Nokwe was the first person of Black African descent to be admitted to the Bar. Nokwe's role in the liberation struggle and his death in exile are well known. Duma Nokwe was honoured by the erection of his bust in the grounds of the Johannesburg Bar Group that bears his name in memoriam. Nokwe signed the Book on 9 March 1956. The minute reflects the values of the various decision makers at the time. He was admitted to membership, the colour bar having been abolished in 1950, as mentioned above, he could use the library, but was not allowed into the common room. (See Browde and Selvan: Supra, at pp 9- 13) Nokwe was, subsequent to becoming a member, harried by the State and prevented from taking up chambers, on the premise that he ought to 'be among his own people'. (See: Peter Pauw: 'Apartheid and the Bar', Consultus, 1992, April, p 22)

However, it is questionable whether it is true that the Johannesburg Bar, as a distinct Society of Advocates, was truly 'founded' then. The genesis of what we call the Johannesburg Bar is far more complex. (See: R L Selvan: 'Early Days at the Johannesburg Bar', Consultus, 1994, October, P115). This is one among many other curious or intriguing facts which emerge from poring over the archival records.

Do we want Blacks in our Bar (again)? The first Black member Duma Nokwe was the first person of Black African descent to be admitted to the Bar. Nokwe's role in the liberation struggle and his death in exile are well known. Duma Nokwe was honoured by the erection of his bust in the grounds of the Johannesburg Bar Group that bears his name in memoriam. Nokwe signed the Book on 9 March 1956. The minute reflects the values of the various decision makers at the time. He was admitted to membership, the colour bar having been abolished in 1950, as mentioned above, he could use the library, but was not allowed into the common room. (See Browde and Selvan: Supra, at pp 9- 13) Nokwe was, subsequent to becoming a member, harried by the State and prevented from taking up chambers, on the premise that he ought to 'be among his own people'. (See: Peter Pauw: 'Apartheid and the Bar', Consultus, 1992, April, p 22)

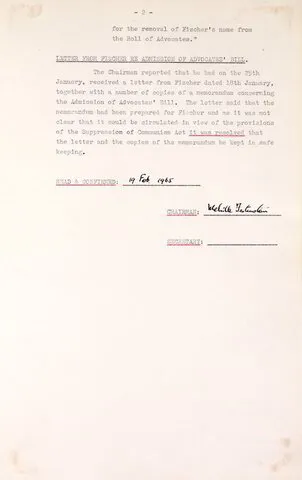

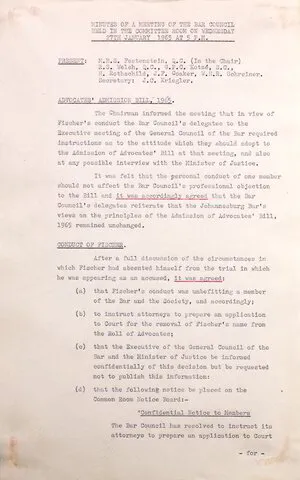

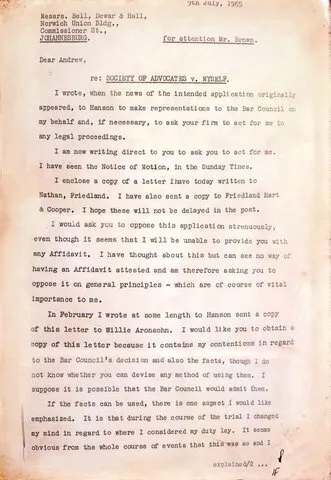

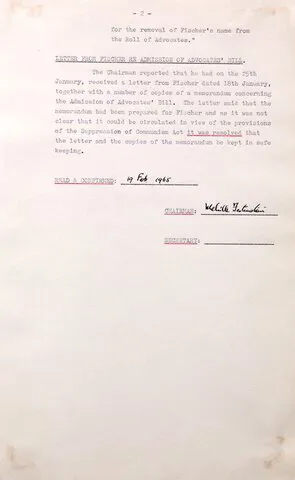

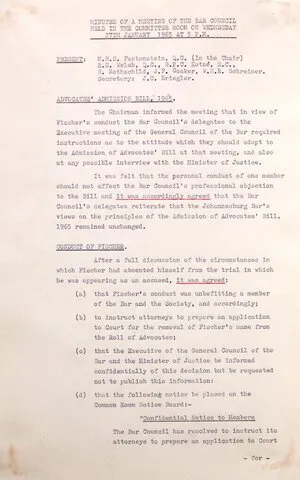

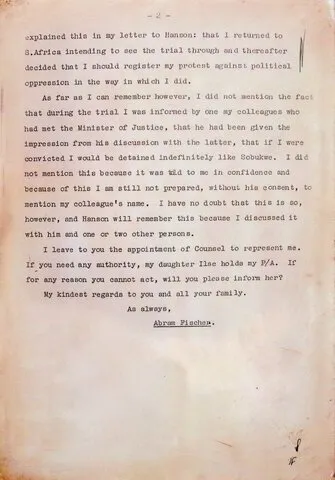

Do we want this man in our Bar? The Striking off of Bram Fischer. These documents record perhaps the most infamous decision of the Bar Council: the resolution to apply to have Bram Fischer’s name struck off the Roll of Advocates on the grounds that he estreated his bail whilst on trial for his involvement in the resistance to Apartheid. No member of the Johannesburg Bar could be found who was willing to move the Application. In this letter of 9 July 1965, Fischer explains his change of mind about standing his trial. The episode has been addressed by Gilbert Marcus and Janet Kentridge: ‘The Striking off of Abram Fischer QC’, in The Johannesburg Bar: 100 years in pursuit of excellence, Durban: LexisNexis Butterworths, 2002, p 45. (See also: Steven Clingman’s Bram Fischer: Afrikaner revolutionary, Cape Town: David Philip, 1998. In 2004 in terms of special legislation and with the unqualified support of the Johannesburg Bar, Fischer’s name was posthumously restored to the Roll. (Rice and another v Society of Advocates of South Africa (Witwatersrand Division) 2004 (5) SA 53 (W). The full history of this episode awaits an author.

Do we want this man in our Bar? The Striking off of Bram Fischer. These documents record perhaps the most infamous decision of the Bar Council: the resolution to apply to have Bram Fischer’s name struck off the Roll of Advocates on the grounds that he estreated his bail whilst on trial for his involvement in the resistance to Apartheid. No member of the Johannesburg Bar could be found who was willing to move the Application. In this letter of 9 July 1965, Fischer explains his change of mind about standing his trial. The episode has been addressed by Gilbert Marcus and Janet Kentridge: ‘The Striking off of Abram Fischer QC’, in The Johannesburg Bar: 100 years in pursuit of excellence, Durban: LexisNexis Butterworths, 2002, p 45. (See also: Steven Clingman’s Bram Fischer: Afrikaner revolutionary, Cape Town: David Philip, 1998. In 2004 in terms of special legislation and with the unqualified support of the Johannesburg Bar, Fischer’s name was posthumously restored to the Roll. (Rice and another v Society of Advocates of South Africa (Witwatersrand Division) 2004 (5) SA 53 (W). The full history of this episode awaits an author.

Do we want this man in our Bar? The Striking off of Bram Fischer. These documents record perhaps the most infamous decision of the Bar Council: the resolution to apply to have Bram Fischer’s name struck off the Roll of Advocates on the grounds that he estreated his bail whilst on trial for his involvement in the resistance to Apartheid. No member of the Johannesburg Bar could be found who was willing to move the Application. In this letter of 9 July 1965, Fischer explains his change of mind about standing his trial. The episode has been addressed by Gilbert Marcus and Janet Kentridge: ‘The Striking off of Abram Fischer QC’, in The Johannesburg Bar: 100 years in pursuit of excellence, Durban: LexisNexis Butterworths, 2002, p 45. (See also: Steven Clingman’s Bram Fischer: Afrikaner revolutionary, Cape Town: David Philip, 1998. In 2004 in terms of special legislation and with the unqualified support of the Johannesburg Bar, Fischer’s name was posthumously restored to the Roll. (Rice and another v Society of Advocates of South Africa (Witwatersrand Division) 2004 (5) SA 53 (W). The full history of this episode awaits an author.

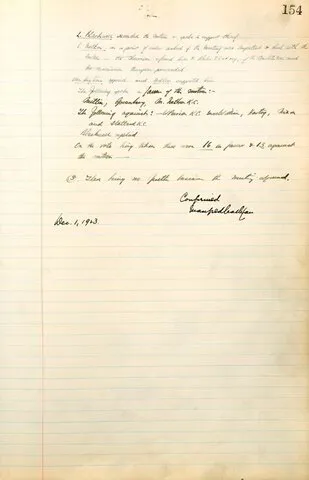

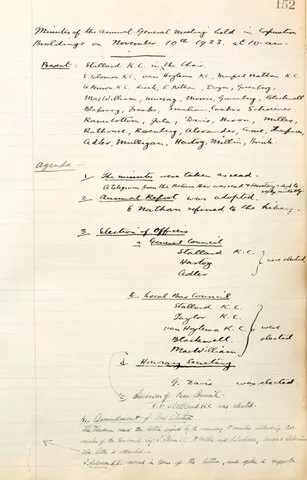

The Race and Colour Bar served for generations to underpin the segregationist preferences of White Dominated South Africa. In general the legal profession was no exception. Among the Bars of the Apartheid era, only the Cape Bar never had a racial qualification to membership. On 10 November 1923, the Johannesburg Bar and the Pretoria Bar were still mere parts of one Society, albeit with a degree of parochial self regulation being practised. The Johannesburg members debated an abolition of the Colour Bar which was approved by 16 votes to 13. The victory of the Non-Racialists was temporary. A joint meeting of the combined Bar on 1 December 1923 rescinded it. The expunging of the Colour Bar was taken up again in the early 1950s when the Johannesburg Bar had unequivocally separated itself from the Pretoria Bar. A compromise resulted in which no Colour Bar was prescribed for per se, but access to the library and the common room fell to be regulated. (See Jules Browde and Ronnie Selvan : ‘The Johannesburg Bar: a Largely Anecdotal History from 1940’ in The Johannesburg Bar: 100 years in pursuit of excellence, Durban: LexisNexis Butterworths, 2002, p3) After three attempts which had failed to secure the two thirds majority needed to amend the Constitution the Pretoria Bar abolished the Colour Bar in the early 1980s.

The Race and Colour Bar served for generations to underpin the segregationist preferences of White Dominated South Africa. In general the legal profession was no exception. Among the Bars of the Apartheid era, only the Cape Bar never had a racial qualification to membership. On 10 November 1923, the Johannesburg Bar and the Pretoria Bar were still mere parts of one Society, albeit with a degree of parochial self regulation being practised. The Johannesburg members debated an abolition of the Colour Bar which was approved by 16 votes to 13. The victory of the Non-Racialists was temporary. A joint meeting of the combined Bar on 1 December 1923 rescinded it. The expunging of the Colour Bar was taken up again in the early 1950s when the Johannesburg Bar had unequivocally separated itself from the Pretoria Bar. A compromise resulted in which no Colour Bar was prescribed for per se, but access to the library and the common room fell to be regulated. (See Jules Browde and Ronnie Selvan : ‘The Johannesburg Bar: a Largely Anecdotal History from 1940’ in The Johannesburg Bar: 100 years in pursuit of excellence, Durban: LexisNexis Butterworths, 2002, p3) After three attempts which had failed to secure the two thirds majority needed to amend the Constitution the Pretoria Bar abolished the Colour Bar in the early 1980s.

Geffen’s suitability was debated. The fact that her husband was an attorney provoked reservations about her eligibility. It was not until 1926 that a woman became an attorney. A concern about an advocate with a wife who is an attorney has never arisen. Allowing women into the common room remained an issue as late as the 1960s.

Do we want this man in our Bar? The Striking off of Bram Fischer. These documents record perhaps the most infamous decision of the Bar Council: the resolution to apply to have Bram Fischer’s name struck off the Roll of Advocates on the grounds that he estreated his bail whilst on trial for his involvement in the resistance to Apartheid. No member of the Johannesburg Bar could be found who was willing to move the Application. In this letter of 9 July 1965, Fischer explains his change of mind about standing his trial. The episode has been addressed by Gilbert Marcus and Janet Kentridge: ‘The Striking off of Abram Fischer QC’, in The Johannesburg Bar: 100 years in pursuit of excellence, Durban: LexisNexis Butterworths, 2002, p 45. (See also: Steven Clingman’s Bram Fischer: Afrikaner revolutionary, Cape Town: David Philip, 1998. In 2004 in terms of special legislation and with the unqualified support of the Johannesburg Bar, Fischer’s name was posthumously restored to the Roll. (Rice and another v Society of Advocates of South Africa (Witwatersrand Division) 2004 (5) SA 53 (W). The full history of this episode awaits an author.

Do we want this man in our Bar?

The Striking off of Bram Fischer

These documents record perhaps the most infamous decision of the Bar Council: the resolution to apply to have Bram Fischers name struck off the Roll of Advocates on the grounds that he estreated his bail whilst on trial for his involvement in the resistance to Apartheid. No member of the Johannesburg Bar could be found who was willing to move the Application. In this letter of 9 July 1965, Fischer explains his change of mind about standing his trial. The episode has been addressed by Gilbert Marcus and Janet Kentridge: The Striking off of Abram Fischer QC, in The Johannesburg Bar: 100 years in pursuit of excellence, Durban: LexisNexis Butterworths, 2002, p 45. (See also: Steven Clingman

Do we want this man in our Bar?

The Striking off of Bram Fischer

These documents record perhaps the most infamous decision of the Bar Council: the resolution to apply to have Bram Fischers name struck off the Roll of Advocates on the grounds that he estreated his bail whilst on trial for his involvement in the resistance to Apartheid. No member of the Johannesburg Bar could be found who was willing to move the Application. In this letter of 9 July 1965, Fischer explains his change of mind about standing his trial. The episode has been addressed by Gilbert Marcus and Janet Kentridge: The Striking off of Abram Fischer QC, in The Johannesburg Bar: 100 years in pursuit of excellence, Durban: LexisNexis Butterworths, 2002, p 45. (See also: Steven Clingman